Ever since the introduction of cameras that were capable of producing quality images at high ISOs, night photographers have understandably been obsessed with photographing the Milky Way. For the first time in the history of photography, it was possible to make images of the starry night sky with short enough exposures to register stars as points of light rather than as star trails. It’s hard to understate the significance of this development, as it allowed us for the first time to see in a photograph the densest part of the Milky Way galaxy in the context of our place in the universe.

Keys Desert Queen Ranch, Joshua Tree National Park, 2018. Nikon D750, Sigma 24mm f/1.4 lens. 15 seconds, f/2.8, ISO 5000.

Beginning in late 2008 with Nikon’s introduction of the D700 and then the D3S a year later, photographers began making nighttime exposures in nature by starlight. By using the previously unheard-of ISO of 6400 with an f/2.8 lens, one could expose the landscape under a starry sky for 20 or 30 seconds and end up with a clear image of the galactic core of the Milky Way in all its glory. In the decade since, even entry-level cameras have become capable of producing decent-quality images at high ISOs, making astro-landscape photography accessible to almost anyone with a tripod.

Today, such images are commonplace enough to be taken for granted by people who have never stood under a sky dark enough to see the Milky Way with their own eyes. I’m reminded of Edward Steichen’s images of Rodin’s Balzac taken by moonlight in 1908. The authenticity of these remarkable images was questioned repeatedly because it was believed to be impossible to make photographs by moonlight.

Edward Steichen, Rodin’s plaster cast of his Balzac Sculpture, photographed by moonlight in 1908. Some of the earliest extant photographs made by moonlight are Steichen’s series of Rodin’s sculpture made in France in 1908 over a period of three nights. Steichen experimented with a range of exposures and lighting, resulting in a series of images that are now considered among his most important works.

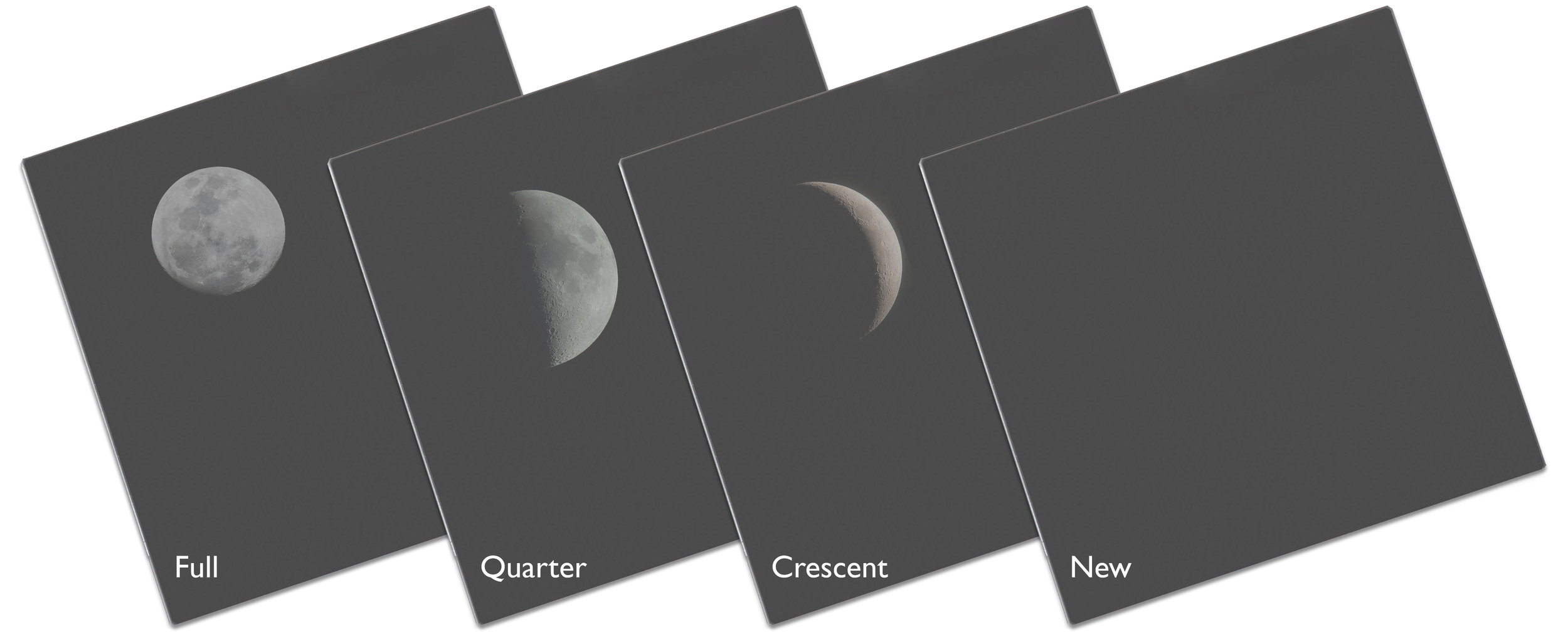

Fast-forward to today and it feels like the concept of night photography is synonymous with astro-landscape, the term we now use for short-exposure high-ISO photography of the night sky. Most night photography workshops are planned around the new moon phase when the sky is darkest, and we giddily await the return of “Milky Way Season” (which coincidentally is just starting as I write this). In April, the galactic core rises above the horizon very late at night, and those who venture out two or three hours before dawn will be rewarded with the rich sight that the rest of us have to wait until late May to see at the “more reasonable” time of two hours after sunset when the sky first gets dark.

However, as all of the images made before the era of astro-landscape photography have taught us, night photography is about much more than just the Milky Way. This is a point I discussed in this space last summer (see “Beyond the Milky Way”). I ended that piece suggesting that night photographers create images that are “about more than just that great big galactic cloud in the sky.”

That sentiment is something I’d like to elaborate on now. The remainder of this article is about the attitudes and approaches of working in different nighttime conditions.

Urban Night Photography

Most people’s first attempts at night photography are made in brightly lit urban environments because that is where most of us live. Photographically speaking, the city is a sea of darkness punctuated with pools of light, and the main challenges are finding light that’s interesting and controlling contrast in the scene.

An SUV waits at the rail crossing, Houston, Texas, 2011. Canon 5D Mark II with a 50mm f/1.4 lens. 15 seconds, f/8, ISO 200. Everything came together in this spontaneous image–– the timing of the train, the composition and the lighting. The red warning light at the crossing provides a color accent and the cool xenon headlights of the SUV illuminate the passing train.

Broad cityscape images made at night often yield disappointing results. Images can be exposed for the overall scene, which leads to clusters of blown-out highlights or to dark, underexposed scenes with puddles of well-exposed highlights near the light sources. Learning to “see” what works for urban night photography is a skill that takes some time to develop.

In my own experience, I tend to see light before subject matter in these conditions. The alluring combination of different-colored light sources or the strong interplay of light and shadow draw me to a scene first, and then I try to find an interesting composition that takes advantage of that light. The best photographs are the ones where the light and subject matter complement each other. In situations with a dominant monochromatic light source, such as low pressure sodium vapor or mercury vapor, I often plan to convert to black and white. The quality of light from these sources is usually appealing only when used in conjunction with a contrasting light source.

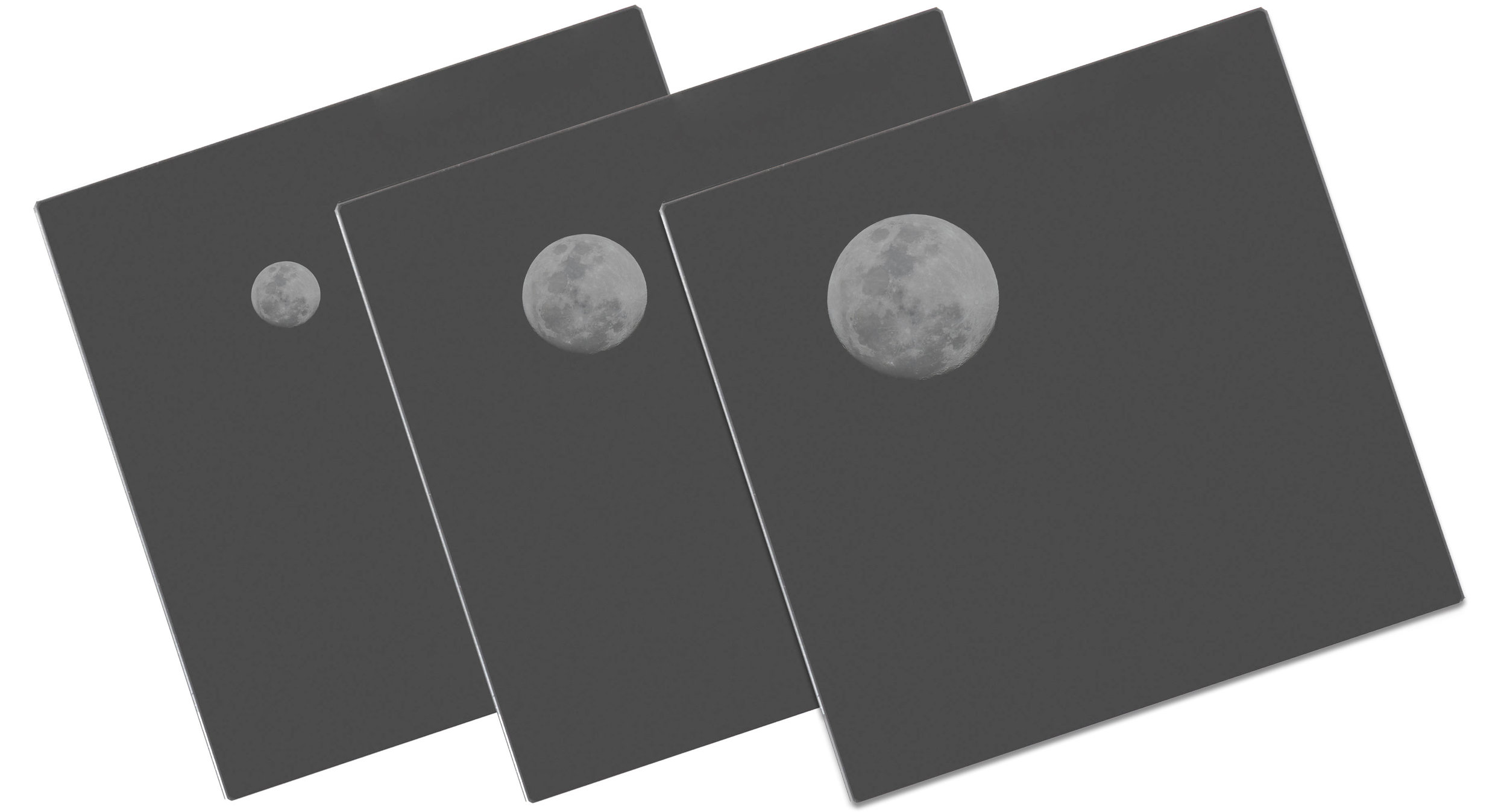

Photographing By Moonlight

When I first began teaching night photography back in the late 1990s, workshops were always scheduled around the full moon, because film and early digital cameras were not capable of making usable images by starlight. Exposures of 15 minutes to an hour or more were the norm. The moonlit landscape is a subtle environment, and one that naturally leads a photographer to slow down and quietly observe the world around them. The romantic notions often associated with the night––loneliness, solitude, mystery and danger—can easily be appreciated by a long walk alone under a full moon. The best photographs made by moonlight often reflect these sensitivities.

Study Butte, Texas, 2007. The moon rises behind a rock formation in the Texas desert. I achieved careful exposure and backlight by placing the rising moon behind the rock, which made this a much more interesting photograph than it would have been if it were front-lit and fully exposed. Canon 5D, lens unrecorded. 268 seconds, aperture unrecorded, ISO 100.

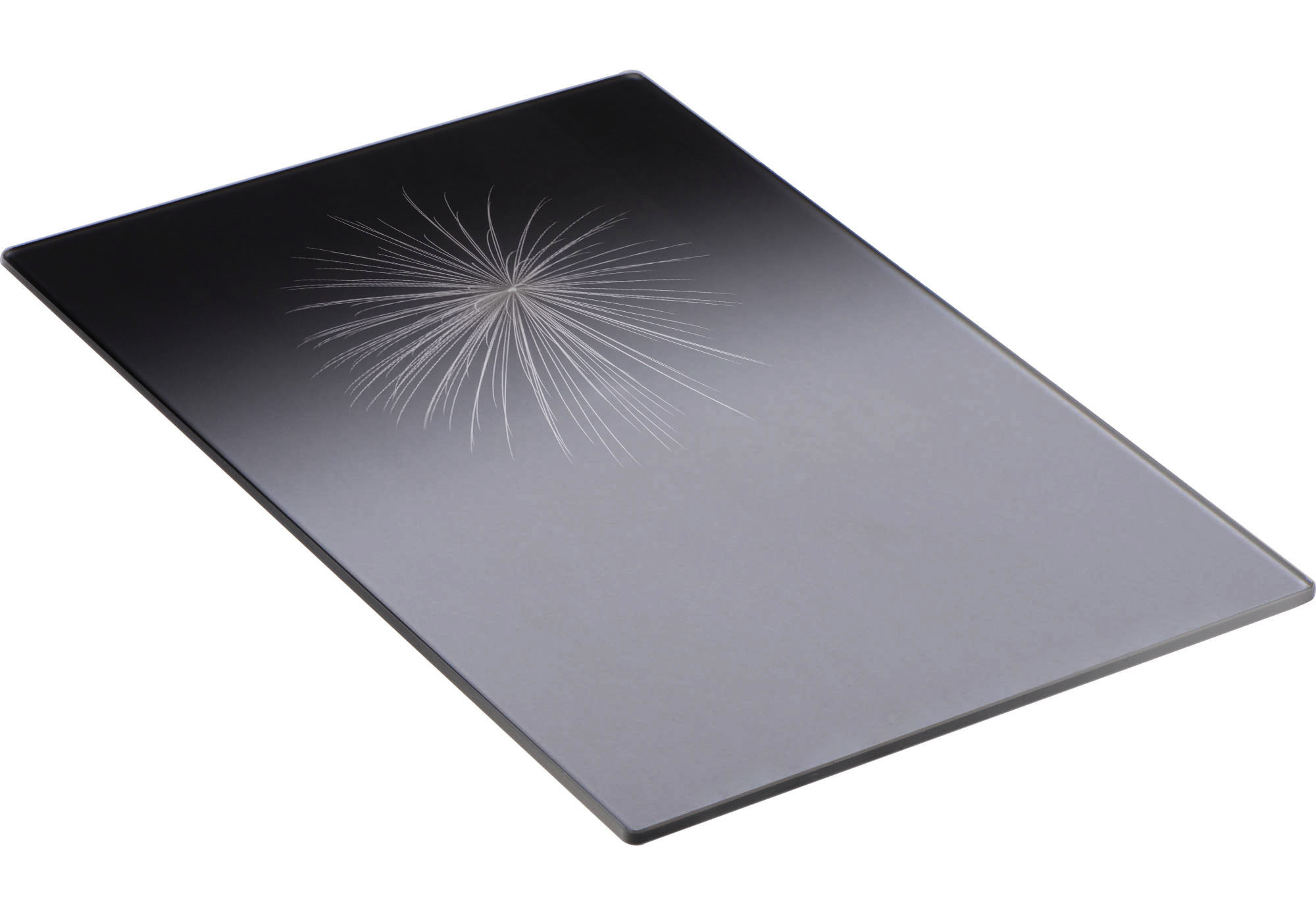

In contrast, fully exposed moonlit images often lack those very qualities that make moonlight special. If one follows traditional exposure guidelines and exposes for a right-biased histogram, any sense of mystery is lost and the result is a strangely bluish scene that looks like weak sunlight. I often say that a good night photograph leaves the viewer with more questions than answers. Rather than revealing everything there is to know about a scene, a successful moonlit image pulls the viewer into the scene, and it evokes that irresistible but slightly uneasy voyeuristic feeling of being somewhere or doing something that we shouldn’t. Careful underexposure, supplemented with well-conceived light painting, can lead to powerful images that are suggestive rather than revelatory.

Astro-Landscape Photography

I’ve often thought of those first few years of astro-landscape photography in the same way as the earliest incarnations of Adobe Photoshop, when filters and silly composites ruled the day, because We Could. Another example might be the heady days when Photomatix was first released, along with those briefly seductive and garish HDR images we are all trying to forget. Perhaps it wasn’t quite that bad, but the idea was the same.

The Discovery, Death Valley National Park, 2015. Nikon D750, Tamron 15-30mm f/2.8 lens at 26mm. 25 seconds, f/3.5, ISO 6400. The combination of bizarre subject matter and light painting make this photograph about more than just the Milky Way. There’s a story here, and the viewer is left with more questions than answers after studying the image.

Likewise, astro-landscape photography was something new, and there was a pervasive energy to explore and test the limits–– the very qualities that lead to advances in art and science in the first place. Now that we are a bit more accustomed to seeing and photographing the Milky Way, galactic imagery has become a bit more sophisticated. Technically, it’s a relatively straightforward process to make a galactic core photograph. Be in the right place at the right time, point your camera in the right direction, focus carefully, and make an exposure.

What makes for the most successful images is context. Rather than just a simple horizon line and starry sky, strive for more complex images where the Milky Way core is just one element of the photograph. Compose an image where that element relates to the foreground, and use the foreground to convey the scale of the night sky and all those stars. Pay attention to the principles of design, and place the various elements smartly within the confines of the image frame the same way that you would with any other good photograph.

Bring It Home, Make It Yours

Some people have strong preferences about where and when they like to photograph at night. Perhaps the energy of the city at night, the pensive solitude of the moonlit landscape or the awesome grandeur of the Milky Way in one of our great national parks is what most attracts you. By all means, follow your heart, and do what you love. Just know that great night photographs can be made at any time of the year and during any phase of the lunar cycle, in the middle of Manhattan or deep in Yosemite.

Different skills or approaches may be required. No self-respecting daytime photographer would limit themselves to photographing at only certain times of the month or during only a few months of the year, and neither should you. Be an anytime, anywhere photographer and make the most of the conditions that you find before you.