What is the best way to master a skill? Typically the first steps are to study the subject and then gain comfort applying that knowledge to real-world experience. However, there is a missing X-factor that can lead us down so many different paths of knowledge. That is collaboration.

We at National Parks at Night have been preaching the importance of collaboration since Day 1. Our whole business model is dependent upon it, as is the experience we offer. We almost always provide two instructors to lead a workshop and try to mix up different combinations that will each yield a unique vibe to the overall experience. We encourage our students to work together and each take turns directing or light painting. A new aspect that we have been experimenting with, and that came together quite spontaneously, is working on a larger-scale collaboration. See our recent post about how our first Joshua Tree workshop did panoramic light painting as a group.

When I taught my first workshop many years ago, part of my proposal was that I co-teach the workshop with Tim Cooper. Tim is not only a good friend, but someone whose photography knowledge and general demeanor I respect very much. We each had different strengths that complemented one another, and not only did the students gain a wealth of knowledge from the workshop, but Tim and I also inspired each other.

“You gain knowledge from each experience—good or bad. If you study and learn from that, better photographs aren’t far away.”

Night photography can very much be a solo effort, whether that means you are shooting alone or going with a group to the same location and just splitting up to hone those night visions. I think this is a very common and old-school approach. With astro-landscape we are looking for strong foregrounds or landscapes, and then framing them creatively against the backdrop of the night sky. We are also seeing more and more people add the human element to their night photography, and that of course is a collaboration.

Personal Collaborations

I remember the first portrait I took of my then-hopeful girlfriend, now wife, Nancy. She knew I was a budding B&W photographer and asked if I could take some portraits of her prior to attending a big fashion event in San Francisco.

At the time, I was doing a lot of portrait work but obviously had little “fashion photography sense.” An early and continual inspiration was Duane Michaels, who created wonderful storyboard fantasies about human interactions. I had recently purchased the Lubitel twin lens camera, a fantastically plastic version of the Rolliflex. You could easily do multiple exposures by just cocking the shutter without forwarding the film. So I asked Nancy to strike three different poses within the boundaries I set. Let’s just say that everything clicked and we have been collaborating ever since.

Another great collaboration, also from the SF film days, was with good friends Peter and Jen. We used to plan shoots every month—Jen would bring a variety of props, costumes and ideas, and Peter and I would set up the shoot.

My favorite experience that came out of our many shoots was the “Angel in the Subway.” We scouted that location and were aware of when it was safe to walk on the tracks. We knew we had to work quickly because the authorities could kick us out at any time. The whole shoot lasted around 10 to 15 minutes and the resulting image became our holiday card for years to come!

When I moved to New York City, I helped start a couple of photo meetup groups that would either schedule early morning shoots or impromptu one-night gallery shows. It was a ton of fun, but it was mainly a bunch of us sharing our individual visions. When I was introduced to Matt Hill and we discovered our passion for night photography was mutual, sharing and collaborating started moving furiously forward!

Matt and I immediately started shooting and experimenting with bending time! We asked “What if” a lot and re-approached our styles of night photography with childlike eyes. Several wonderful projects were born out of our continual collaborations—my favorites are our yearly workshops on Bannerman Island, Matt’s time-bending night paper portraits, and of course National Parks at Night, which was concocted one evening when we were both sitting under the stars as our cameras were ripping long exposures.

Coaching Collaboration

How do you teach collaboration? Because it either works or it doesn’t. You can really sync with some people and might have to just walk away from others. But I strongly feel that you gain knowledge from each experience—good or bad. If you study and learn from that, better photographs aren’t far away.

Bouncing ideas off of each other prior to getting out in the field is a great first step to see if you gel. Like-minded people aren’t always the best collaborators—ideally we want to complement each other and bring a unique idea, question or solution to the table.

We like to arrive to our locations during the day—either a couple of hours before sunset or during midday. We use that time to scout the locations and really walk around the scene to figure out the shot. We are often drawn to the obvious, but more dramatic possibilities might be just around the bend.

For example, at the last night at our second Joshua Tree workshop, we invited anyone who wanted to collaborate on a group shot to meet Lance and I at 10:30 p.m. Most of the class joined and we divided the group into two. We chose locations and set a 20-minute time limit for each group to shoot at one location and then switch to shoot the other.

Below, Lance and I share both teams’ behind-the-scenes process and the images that came out of this.

Two Cars

Gabe: Our first subject was two cars hidden behind some rocks. Without setting up our tripods we walked around the scene. The point of view seemed pretty obvious and could have been captured with a superwide-angle lens. However, I wanted to tell the story of how these cars were nestled under the rock hill and under the night sky. I suggested a four- to five-shot panorama that would encapsulate the location with minimal distortion from a wide-angle lens.

I zoomed my Nikon 14-24mm lens to 24mm, leveled my tripod and head with a panoramic level base, and took some quick test shots to see if it would work. We tried compositions that included the moon, but decided to exclude it as it detracted from the real story.

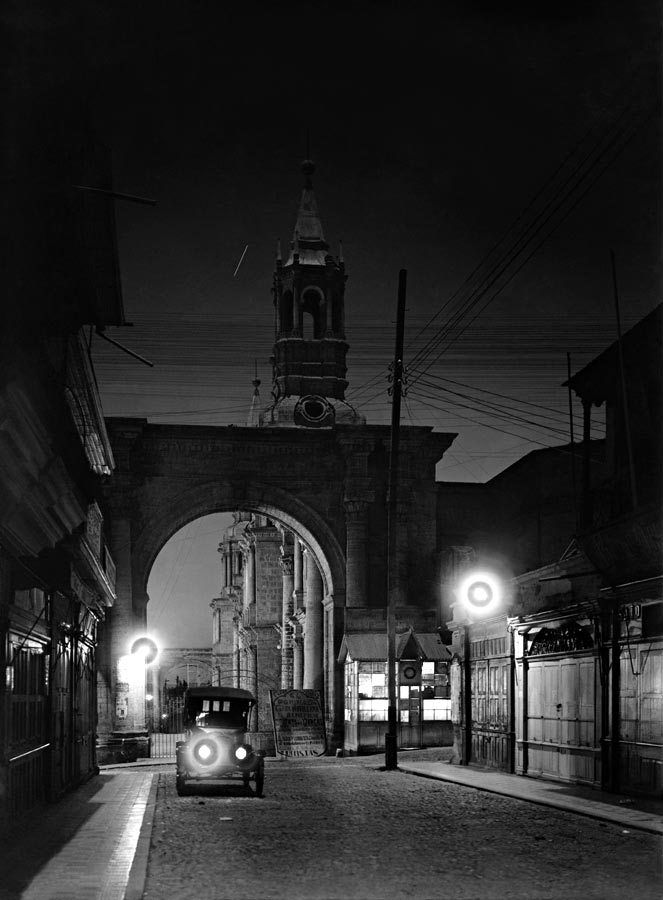

Collaborating in Joshua Tree National Park. Photos by Susan Wales.

Sandra and Beth experimented with some subtle light painting to open up shadow separation. We decided to go for a more natural-light approach rather than adding light for surreal effect. Susan, who was taking some amazing night portraits, captured some great behind-the-scenes photos of the shoot, and Robin set up next to me so we could have two points of view for the panoramic scene.

We did three to four takes where I was calling out when we were open so our light painters could time their lighting accordingly. We did two takes and kept things simple. I was pretty pleased with our results.

Another Two Cars

Lance: Somehow when the group split up to do the collaborative shots, everyone fell along gender lines, and Gabe, ladies’ man that he is, ended up working with the women. The men’s group consisted of Klaus, Rick, Terry, Steve and Hadley.

The guys decided right away that they wanted to do something different from the previous week’s workshop attendees, who had created the panorama of the ranch. Everyone was drawn to the cars, and we walked around checking out the various wrecks looking for our shot. We agreed upon the Plymouth and the Dodge, both of which were mid-1940s cars facing in opposite directions.

Klaus was elected to direct this image, and he framed it fairly tight, as a straight-forward composition facing west. The moon was high in the sky and casting shadows on the foreground. We decided to let the moon do most of the work. Terry took on the task of lighting the interiors, with a short string of warm-white LED Christmas lights on the front seat of each car.

Klaus used his previous experience photographing in junkyards to expertly light the headlights of the Dodge, and Steve raked a light against the back end of the Plymouth and then softly filled in the shadows on the back ends of both vehicles with reflected incandescent light. The warm color balance of the added light contrasted nicely with the naturally cool moonlight, and set the mood perfectly.

Three Cars

Gabe: Our next collaborative challenge was a cluster of three rusted-out cars. As we walked around the scene the moon was shining from one side, and as obvious a shot it was, we quickly assessed that the light was just to direct and flat. However, when we walked 180 degrees to the other side, the moon created a nice backlight and gave us lots of shadows on the front to be creative with while light painting.

Sandra loves abandoned old cars and started talking about how she saw the shot. It is always good to have a director who oversees the collaboration, so we gave Sandra the reins.

Photos by Susan Wales.

After setting up at a low angle and firing off a couple of test shots, with Beth confirming focus and composition, we were ready to practice painting. We knew we had to paint from both the right and the left of the cars. We used the same flashlight and Sandra directed how the light was falling so we could adjust our angles and timing. We also saw a need for a little backlight between the cars to separate them a bit more, so I jumped in and lit from a low angle so the flashlight wouldn’t be seen by the camera.

Because the light painting was a bit complex with three people working from three different angles, Sandra was only exposing for the light painting, reviewing the image and then giving us feedback. The overall exposure was 2 minutes but we were generally done with the painting in half that time. This let us repeat our motions and save time so that the final exposure was pretty much spot-on!

Two Cars and A Boulder

Lance: We chose two other cars that were spaced a little further apart, and we used a similar plan of attack. For this, Hadley was the director, and he set up his camera in what we determined to be the best spot to show these cars in the context of their final resting places. Vince also joined us for this second image.

This second shot minimized the moon shadows, but emphasized the location and the way that the cars were situated in the landscape. Everyone took turns lighting the various parts of the scene, and we ended up with a photograph that had a similar mood and feel to the first. The two work nicely together side by side.

The collaborative process was fun, and everyone got something out of the experience. I always encourage collaboration, but such collaborations tend to be smaller groups—pairs or trios. In this case, the seven of us managed to work together and all find a way to contribute. These shots were relatively simple and contained within a small area, but the seven of us managed to work together and all find a way to contribute. At the end, we even made a group portrait to commemorate the occasion!

Joshua Tree light painting Group No. 2.

Final Thoughts

Collaboration is definitely at the forefront of my mind right now. We at National Parks at Night have been excited with our early experiments during the workshops and we can’t wait to see how that continues to grow. On a personal level, I want to engage and work with more artists and opposites to see what new creative paths can be explored!