Rarely do I find a tool that causes a paradigm shift in creativity or efficiency. The Luxli Viola 5" LED light is one of them. Why? Simply put, I can be very, very deliberate and accurate with the color of light I choose when light painting.

Prior to this, only a few tools really made me say, "Now I can really do something different/better." Those were:

- a 4x5" view camera (total control over the image)

- PocketWizard flash triggers (those changed photography forever, and for the better)

- a light/flash meter (because I could focus on being creative instead of finding the right exposure)

- the on-camera histogram (this unlocked the High ISO Test so we can all nail a proper long exposure)

- the Pixelstick (because, damn … its potential for creativity as a light writing and painting tool is limitless)

Each one of these tools opened new realms of creativity. Once I started using them, I was eager to experiment, and I found new efficiency in what I could do (well, except for view cameras—they slowed me down in a truly terrific way).

As with these other tools, the single most important characteristic of the Luxli Viola is that it solves a technical problem. The result is that it allows me more time to focus on being creative.

The Real Problem this Solves

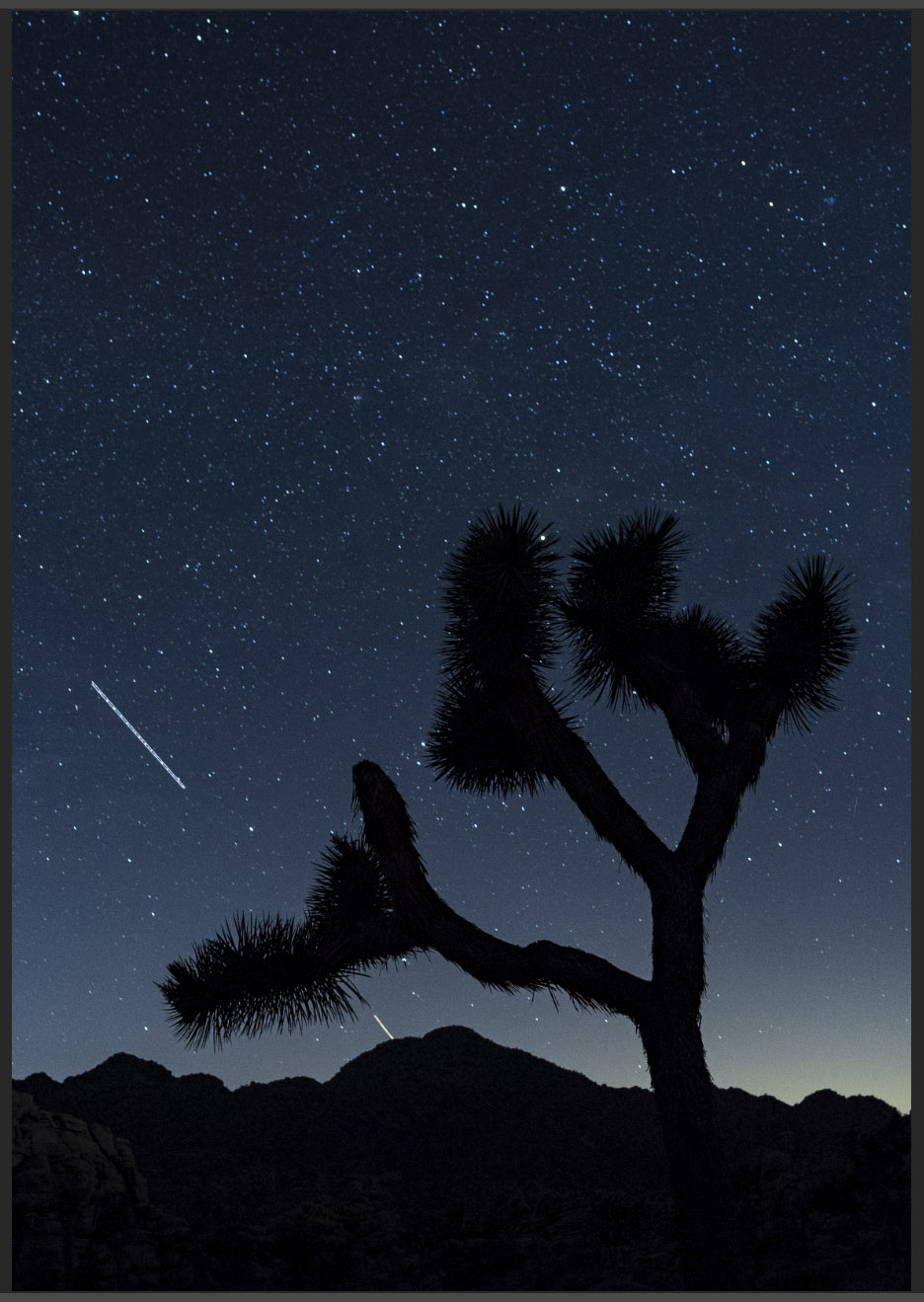

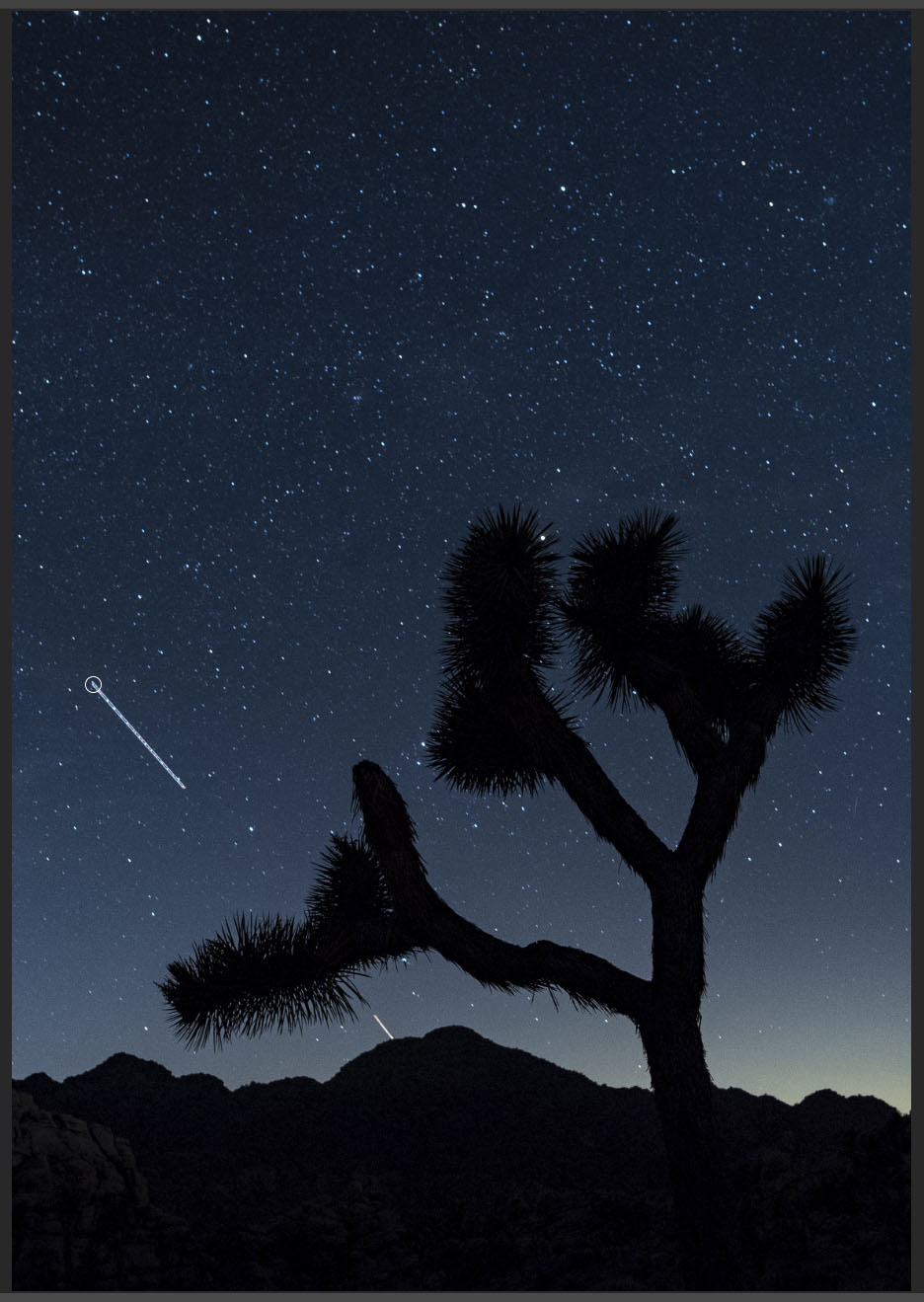

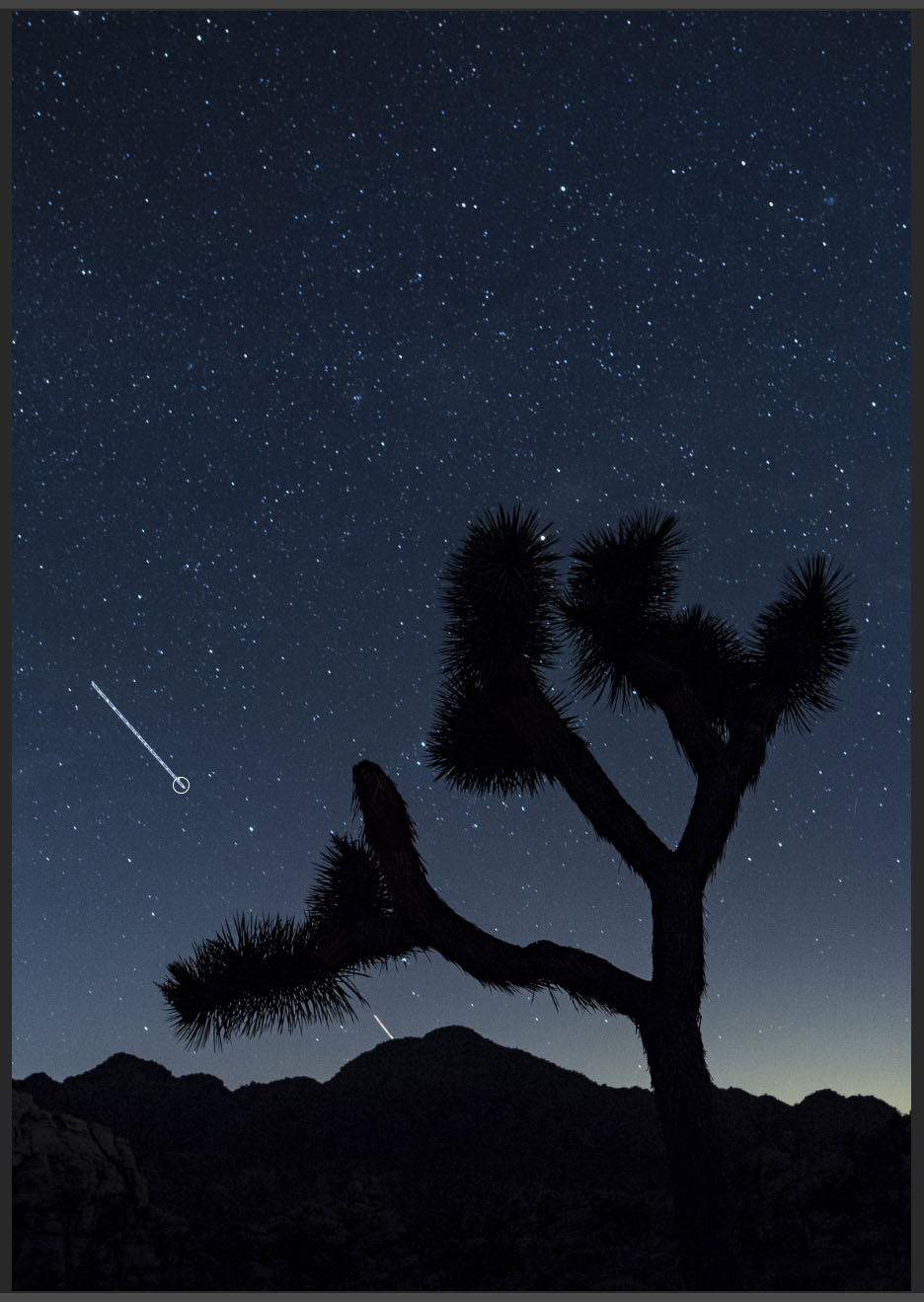

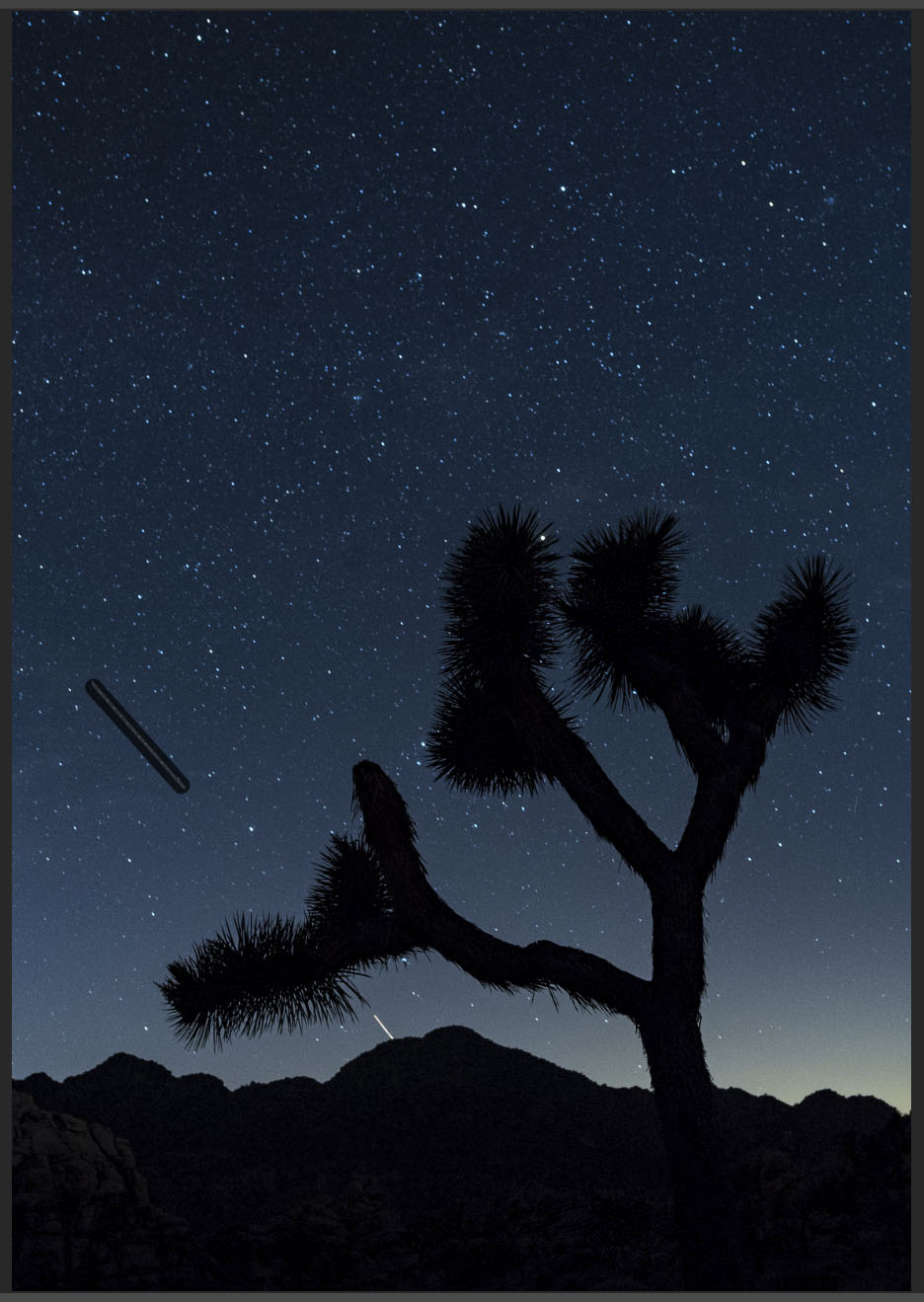

This problem is illustrated best when light painting using multiple flashlights, which often happens when working in a group. In the images below, you can see the color difference between my flashlight and Gabe's:

Note that Gabe's flashlight is warmer than mine. When I choose one flashlight source as neutral at 2600 K, the other is warm. If we had the same model flashlight and same strength and color gels, it would be the same. But we didn't. It doesn't look wrong, but I started to notice when it happened and thinking about how to collaborate better to create group masterpieces. You can even see the difference in the original 4000 K captures in-camera.

My 2017 Self-Challenge

At the beginning of the year I asked myself, "What makes me uncomfortable? What should I be better at doing, but perhaps am avoiding putting time into practicing?"

Well, I am very fond of black and white photography. I love it so much that I practice it almost as exclusively as I do night photography. So I challenged myself to master color. And not just color in general, but being very particular and deliberate with how I use color.

My new BFF

Then in walks this rather humble-looking LED source. There are tons of on-camera LEDs for video. What sets the Luxli Viola apart and directly applies to my night photography is that it 1) renders all color temperatures from 3000 K to 10,000 K and 2) renders any hue on the color wheel that I desire. Why, you may ask, is that so groundbreaking?

Well, I've been gelling flashlights for years and frankly I hate doing it. It's awkward. It reduces the output. Sometimes I lose them. And most of the time, the color correction of blueish LED sources doesn't quite render the 3200 K or 3000 K or whatever warmer tone that I want. Sometimes it's too warm and causes the delicate reds and yellows of my beloved desert features—such as arches and bridges—a bit too garish.

Knowing I can simply roll a dial on this LED panel and nail a color temperature got me so excited.

How I make the sausage

The first place the Viola really made an impact was when shooting Milky Way star point exposures. I'm consistently using a 3800 K white balance to accurately render the galactic core. What if I want a neutral light source for the foreground? Easy. Dial the Viola in to 3800 K.

With a flashlight instead, the illumination may end up too cool with a light CTO gel, or too warm and slightly tinted red with a bastard orange gel. But with this LED, no fuss. If I want something a little warmer, I cheat down to a lower color temperature. If I want cooler, I do the opposite. So easy. If I want to go crazy and use straight hues for color accents, I switch to color mode and dial in any darned color I want.

The only other tool I've heard of that exceeds the Viola is the ProtoMachines LED8, which is a light painter's dream (and a also pretty serious investment at $559). Anyone familiar with Troy Paiva's work has witnessed the power of this tool in the hands of a master. I just discovered that ProtoMachines released the Radium light painting wand, an upgrade to the LED2 that runs only $275. However, I have heard is that patience is sometimes required to obtain one, since they hand-build these tools.

Figure 1. Owachmo Bridge at Natural Bridges National Monument. Shot with a Nikon D750 and Distagon T* 15mm f/2.8 lens. 22 seconds, f/2.8, ISO 6400, blended with a dusk image shot at 78 seconds,

f/2.8, ISO 400.

The Luxli Viola 5" LED is also spectacular when applying the Low-Level Landscape Lighting technique. For the photo in Figure 1, I set the Viola to 1 percent output and placed it below Owachmo Bridge. The panel provided a constant, barely perceptible glow that complemented the exposure time needed for star points and the Milky Way. (This image was then blended with an indigo dusk photo for the shadows—more on that in our recent post, "Finishing Touches: 3 Killer Post-Production Tips For Night Photography.")

Figure 2. Tower Point at Hovenweep National Monument. Split exposure of 22 seconds and 480 seconds, f/2.8, ISO 400.

When it's really hot out, sometimes you have to make two exposures—one for a low-noise foreground, and one for the spectacular dark skies you get in southern Utah in June. For the photo in Figure 2, I made a 480-second exposure to blend with the sky of a 22-second frame. For the long exposure, I didn't to add light the entire time. So I used another of the Viola's cool features: Bluetooth control. I turned on and off the light for a few seconds at the beginning of the long exposure with my phone. How convenient, right?

I placed the LED to craft textures and faithfully render the bricks' delicate colors at the same 3800 K that I'd set my D750 to. I was so confident about the results that I simply sat back and enjoyed the view. ;-)

At Tashi Gomang Stupa (above), we used a Luxli Viola on a low-to-ground tripod at the bottom left corner to illuminate the main body of the structure. The camera and Viola's white balance were set to 3200 K. If you observe at the light spilling out from behind the stupa, you'll see a warmer light from a 1/4 CTO-gelled flashlight. See the difference between a color-corrected source and one that is simply correct?

Now, aesthetics also come into play. I wanted a warmer splash behind, so this was intentional. But the flashlight-plus-gels scenario is limited to what you carry, and also eats time while setting up. I am enamored with starting with a neutral light source and then cooking the color to taste.

Mixing and Matching Color Balances

Because of the I put this to the test in the field at Olympic National Park. At Second Beach, I found a sea stack in the distance with some rocks in a tide pool in the foreground. The tide was coming in and making sweet swirls around the rock. This effect was also aided by the thick foam (which Chris commented wiggled like Jello-O when prodded with a toe).

Figure 3. All images above shot at 26 seconds, f/2.8, ISO 6400 with a Nikon D750 and Zeiss Disatgon 15mm f/2.8 lens. Download a high-res version of this chart here.

Keep in mind that there is no right or wrong when it comes to color temperature. There is knowing what affects your sky and foreground in a manner that you find pleasing. For the scene in the test above, I prefer the 3800 K camera and 5700 K LED. I was surprised by that—I had thought I'd like the 3800/3800 combination. Test and experiment!

Night Portraits

The Viola is also hella cool to use for night portraiture. It's not a flash, so don't expect crispy edges—people do move. But if you use the Viola briefly and your models hold still enough, it can be a great light source.

Figure 4. The B&H marketing crew and astrophysicist Summer Ash at the Atlas Obscura eclipse event in August.

Nikon D750, 22 seconds, f/2.8, ISO 6400. White balance 3800 K (camera and LED).

For the photo in Figure 4, I matched the color temperature of my Viola to my CTO-gelled flashlight at 3800 K. The Viola is on the left of camera and the flashlight is low on the right.

Bonus: Bluetooth!

On top of all this, as mentioned earlier, the Luxli Viola has Bluetooth that allows you to control up to nine lights. When is this useful? When you want to simulate a flash, but can't use one, like for this group photo of our workshop participants at Olympic National Park last month:

I'm operating the lights with my phone behind Chris' back at left. Camera is set on intervalometer. 10 seconds, f/4, ISO 6400.

Wrapping it all up

I am enjoying the process of thinking critically about color and its application. I feel like I've grown as an artist and have another vital tool in my toolbox. I am equally excited about color and black and white imagery, but I think the results were worth going outside my comfort zone. And I'm keeping the Luxli Viola in my bag. Now I have to decide what to vote off the island, since gels didn't really occupy all that much space. ;-)

Here is a recap of the benefits I find using a Luxli Viola:

- Constant light makes it easy to repeat lighting effects, including exact shadows, intensity and placement.

- Choosing a color temperature that matches my color balance in-camera will faithfully render the color of the objects in the scene.

- Choosing a warmer or cooler color temperature can add creative flair.

- It's very light and small.

- When running at 1 percent power (which is most often for me), it will run all night and then some.

- Adding the collapsible diffuser kit gives me a soft snoot to kill light spill at the edges, plus an even softer effect.

There are a few disadvantages, however:

- It's $350* (way more than a good Coast flashlight and gels).

- The optional diffuser kit (which is amazing) is another $100*, or you can get both together for $429*.

- An LED array is many little lights in rows and columns. It will never throw as far as a flashlight with a focused reflector on the front. So, you'll likely not be able to use it as a focusing aid, or for illuminating things very distant, unless you go for a longer exposure, or walk it deep into your frame and point it toward the thing you want to light up.

- It's bigger than a flashlight. (That's a hint! hint! for any manufacturers out there who want to put these features in a flashlight form!)

* At the time of writing, these are the prices listed on B&H. Prices can fluctuate, so check back.

Let's talk about color in the comments! How do you feel about your control and use of color? What tools do you use? How are you challenging yourself to grow?